Dancing Through War, Finding Peace in Yoga

In 2004, I lived in a poor suburb of Damascus, where life was affordable for my parents but full of social challenges like poverty and limited education. I was one of the few students who continued to high school; most of my classmates had to work to support their families, as I was expected to, but I chose to keep studying and working during the school holidays.

Full of energy as a teenager, I took up karate to protect myself in a neighbourhood known for frequent conflicts. One late night, I saw a dance performance on TV that stayed with me — the fluid, powerful movements fascinated me.

A few weeks later, I saw an ad announcing auditions for new dancers to join that same dance company. Despite having no background in dance, I applied and was accepted after a physical test for strength and flexibility. Out of 70 new trainees, I realised I was the only one from the suburbs. This company was prestigious and well-known in the country — a world far from mine: Enana Dance Theater.

We trained three days a week, starting with basic floor exercises. Later, we began ballet training. At 18 years old, coming from a karate background, it was strange at first, especially wearing tight dance clothes in a ballet class — but I slowly adapted. The atmosphere was completely different: open-minded, expressive, and welcoming. It felt like a soft transformation.

I didn’t dare to tell anyone in my neighbourhood, knowing that this was not acceptable, in case they thought I was still training for karate. But when my karate teacher noticed my absence, I told him the truth. Surprisingly, he supported me, knowing that I had little chance in sports within the corrupt world in the Syrian government, especially if I had no connections and was not from a well-known family. He understood how different our worlds were and encouraged me to pursue this new opportunity.

Slowly, I started to be on the stage, first with one small dance piece with a group, and later, over the years, within the whole show. At that time, it had been 4 years in the dance world. I knew all the basics of ballet and had started to join all the shows in the dance company. I really loved dancing, while I first studied as a sports teacher. As everyone in Syria knows, I had to join the military service. I had already delayed it for 3 years, but now I had no official papers to delay it again. But I still had one card I needed to play to delay this nightmare again, which was in the Higher Institute for Drama and Arts, the dance department. But for that, I was already over age. I needed an exception from the Ministry of Culture. I remember that day when I went to the manager and the founder of Enana Jihad and his wife, a Russian ballet teacher, Albina, and told them: “I don’t want to stop dancing and go to the military service,” and I asked him to help me to join the dance department with his connections, since Albina was the ballet dance teacher there as well.

With a very open heart, and with no hesitation, he told me to meet him tomorrow in front of the Ministry office. On the same day of the audition for the dance department, I was surprised when he asked me to come to the minister’s office. He was there waiting for me and introduced me to Minister Ahmad, one of our motivated dancers. He wanted to study and develop himself, and he handed me the acceptance letter. I went directly to the audition. I got accepted into the highest Arts Academy level of Arts in Syria, and when I went home, I couldn’t mention anything about that, knowing that’s not acceptable according to the rules and social taboos. I had my other art circle friends from the dance company and the Arts next to my neighbourhood friends, who I met only on weekends on Friday when I had to stay home, and when I met someone in the street, I always had the answer to their questions — with my sports backpack and the gym.

Having been a student again, I won at least 4 years delay from military service, which I made for 7 years to enjoy a life of dancing in the morning at school and in the evening at the Enana Dance Theatre, and travelling and performing almost every month to a different city or to a different country, escaping the school classes and the exams — till the 2011 revolution in Syria started.

Then the dance shows were fewer or supporting the government propaganda. The minister who gave me an exception defected from the government and joined the ranks of the people’s revolution.

The dance company moved to Qatar, and Qatar was the most visited country we travelled to, and it was the country that supported the revolution in Syria.

The circle of violence became bigger and bigger in Syria, and there were many checkpoints in the streets, almost at every main street in the country. At the checkpoints, trouble started for people who passed through daily, and for me, coming every day from the Damascus suburb and back, I had to pass by at least 5 to 17 checkpoints. They were collecting people for military service, always checking all young men’s IDs and checking the delay, and beginning with verbal harassment due to jealousy because I was still free and they were standing all day long at the same spot. Some of the checkpoints started to pick random people to collect some money or threaten them.

At the same time, the revolution got weapons and they started to ask young people to join them, especially from the countryside where the government no longer had control.

After 3 people from my neighbourhood were kidnapped by people with weapons, it was a clear signal for me to leave the suburb for Damascus.

The day of moving away, I passed by the school where I gave sports classes to get my salary after 6 months teaching. The school was full of displaced families who fled their homes from the bombing of the government forces. I was surprised that there were also armed people who guided me to their leader, accusing me that I was working with the government. After a small talk, he pulled his gun and pointed it to my head, asking me to join the armed revolution. I didn’t know how I controlled myself and had a conversation with him, telling him that I was more effective at my university than holding weapons. And he was happy, and he was convinced of my idea, and he let me go.

I moved to the city. My family was safe because their targets were young people from both sides — the armed revolutionaries who were active in the countryside and suburbs, where there was more poverty and no longer government control, and the government checkpoints taking people who had just finished their studies or someone they didn’t like.

The dean of the Higher Institute of Dramatic Arts was replaced because he had been appointed by the minister who defected from the government, and was substituted with a woman who was highly loyal to the government.

This woman accused me of treason because I used to travel to Qatar, which supports the revolution, and she threatened to write a report to the intelligence services so that I would be detained. On the same day, I asked her to withdraw my request as a third-year student due to family circumstances, explaining that I wanted to focus on my family, to avoid her and to avoid her report against me.

During this year, I chose to work in a hotel where displaced people from the Damascus suburbs could find a safe place in the middle of the city.

In my 4th year of studies, I met Noealia, who was working with the UN staff in Damascus in 2014. We met in a gym room where I used to teach fitness classes after my studies, while she was teaching volunteer yoga to the people who joined her class. When I first saw what she was doing, I refused to join her classes, believing that as a dancer, I didn’t need yoga for my body. But then I tried it, and at Savasana I felt something I had never felt before — something I couldn’t explain. So I came again and again to experience this feeling, escaping the noise of random mortars and the government’s bombardment with artillery and aircraft in the countryside around Damascus.

Especially since the studio was under the ground of a restaurant in the middle of a luxurious neighbourhood in Damascus, only 5 minutes away from the Four Seasons Hotel. This place was the safest place ever for me, and my yoga mates were like my whole world — a space where I felt safe, where I slept, cried and lived, knowing that I could die any moment during the day because of daily mortars in Damascus.

What always made it difficult for me every day when I left home was the thought that, if I got hit by mortars or an explosion, I hoped to die instantly and not be wounded or disabled. The second thought was saying goodbye to my mom, and she would say, “Take care of yourself.” I would joke, “How? If the mortar hits me, I won’t have time to take care of myself — and it hits everywhere.”

One day, I was with my colleagues dancing in the theatre at the Higher Institute of Arts — the Italian Theatre, which is a bit underground. We had closed the doors to isolate ourselves and be able to work without disturbing others. A few mortars hit the building, and a few students were injured and transferred to the hospital. Luckily, the theatre where we were dancing had good sound insulation, and with the music we couldn’t hear anything. The whole building was evacuated except us — no one knew we were still working in a safer place than the other studios. When we left the building and were wondering where everyone was, an old man who used to close late told us what had happened.

Many days, we received SMS messages from our teacher telling us not to come because of heavy mortars in the city, and to avoid certain checkpoints because they were collecting young people to put them in military service after only short training on how to use a gun.

During those days, I kept dancing and joining yoga whenever I could, to let go of the frustration and powerlessness I felt.

In September 2015, Noealia informed me that a Jivamukti teacher was coming to Lebanon for an immersion. Because of the lack of money — and since the payment was in US dollars — I only had $300, all I had saved from dance and travel work where I had to pay for everything myself. I wrote a letter to the studio explaining my situation, telling them I would like to join but didn’t have enough money. With very warm hearts, they welcomed me as a guest.

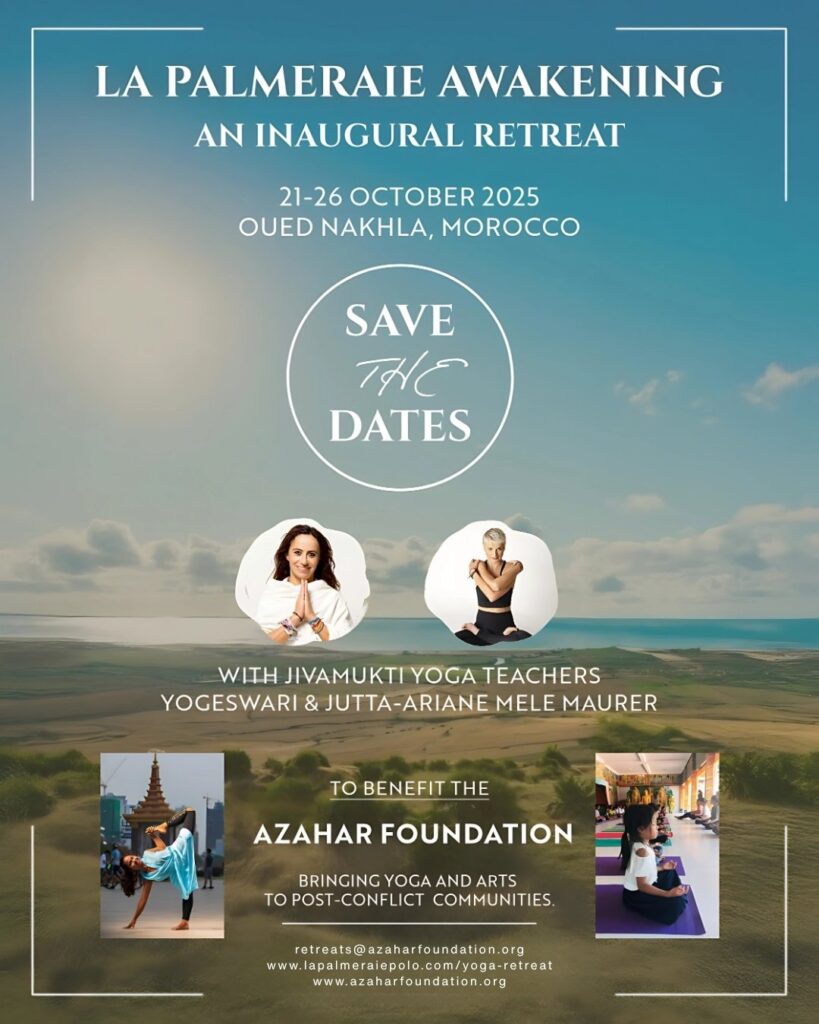

This was the time I met Yogeswari and Rima Rabatha at the Beirut Yoga Souk, in a room full of people coming from all over Europe and the USA. I was the only poor person who had barely attended any yoga classes before. I loved everything about this immersion. I practiced yoga with so many people and shared real stories from Damascus that most people didn’t know except through the news.

At this time, Yogeswari asked me to join the Azahar family. She saw in me a yoga teacher somehow. I wasn’t ready for that; I was only in survival mode. I think I said, “I don’t know.” I didn’t know that I would move soon.

After a few days filled with yoga and connection, I went back to Damascus — but my heart was in Beirut, searching for somewhere far away from the war.

After I finished my graduation project, completed my studies, and started looking for opportunities outside the country. I applied to a study program in Italy and got accepted, but the visa was an issue, so I couldn’t go.

When I got the rejection of the visa in Beirut, I had no place to go. I didn’t want to go back home, so I visited a dance friend with whom I used to dance at Enana in Syria, but he had moved to dance with the Lebanese Dance Theater, which was even more familiar than the one in Damascus and more international.

So I stayed a few days to release and to accept the negative news about the visa thing. During these days, the Lebanese dance company announced an audition for a dancer, so I had an opportunity to join the audition and to move to Beirut.

Moving to Beirut was the safest option for my life. I had less than 1 month of my delay from my study, the military service, and the new rules that I was not allowed to register myself in another kind of study as a first-year student since I had already finished 2. So the only option was to leave the country or to give up and join the killing machine in a country where I was born and grew up.

I still remember that day when I left Damascus, when I couldn’t look back, and I didn’t even say goodbye to my dear friends — just hoping for everyone I love and I know to be safe and to find a way to escape.

The first days in Beirut, I couldn’t sleep well and avoided sleeping next to the windows, afraid that the glass might fall at night because of the bombardment I had seen.

Moving to Beirut and starting a new life dancing at Caracalla — this was a dream for me. Doing yoga at Beirut Yoga Souk was a gift from heaven, and of course, walking without checkpoints and without hearing bombardment every day.

Hard-working, dancing almost 5-6 days per week at Caracalla Dance Theatre with many international dancers — Ukrainian and Russian dancers — doing other work for the theatre like costumes and decoration too, and teaching modern dance at Caracalla Dance School. Travelling with the company to China and to other countries, being able to support my family.

During these years, I kept in touch with Yogeswari and Rima, and they were connecting me with the teacher, the yoga community, and with people. When Yogeswari came to Beirut for a workshop, we met and talked about supporting me to do JTTT.

In 2018, I was ready to do the training, and this required many things — first of them a visa to India. So I went to the embassy in Lebanon to apply for a visa since I had been living there for 3 years already. The Indian embassy in Lebanon told me that I had to go to Damascus for that because I am a Syrian citizen, and there is an embassy there.

I wanted to be in this JTTT so much, and I decided to take a risk and go to Damascus — but not through the normal borders. It was an alternative way to Damascus, where there is no control but military.

During my stay in Lebanon, I met many people and had good contacts with them, so I knew someone who knew someone else who could bring me to Damascus without going through the checkpoints. So the plan was to meet in the middle of the night in Beirut, and someone would come to pick me up in a dark-windowed GMC car. I met this guy and he told me, “Don’t say anything at the border,” and we drove to Damascus. It took 2 hours and 20 minutes. This car didn’t stop at any checkpoints — it was totally the opposite. When there was traffic, the soldiers at the checkpoints stopped all the other cars and let our car pass.

I arrived in Damascus in the neighbourhood where my parents live, where I could reach walking, and this guy told me not to say anything if anyone asked at any checkpoints, because officially I didn’t enter the country. When I stepped out of the car, I realised that this car had no number plate, and everyone looked scared at this car when it stopped.

The next day, I went to the Indian embassy to apply for a visa. The employee saw that I had 1 year of residence in Lebanon and an address in Beirut, and he told me, “You live there, so you can apply for a visa from the country where you live,” and he gave me a letter for the Indian embassy in Lebanon.

At that time, I had less than 3 weeks for the JTTT, and Yogeswari emailed me to check what had happened with me. After visiting my family and the embassy of India, the next day, the same car came and took me the same way to Beirut. Nobody knew anything about it, but the fear I had to get out of Syria again, I couldn’t. discrip.

The driver told me many times to relax and that everything would be okay. “In the worst-case scenario, we call our friend and everything will be alright.” And I trusted that friend very much.

On Monday, I went to the Indian Embassy for the third time. I told them what the embassy in Damascus had said and gave them the letter. The man there told me they needed a minimum of 10 to 20 days to get an answer. But I still had less than 12 days before the teacher training, and Yogeswari texted me again to check. I informed her about what happened and told her I was waiting for the visa.

At last, Yogeswari texted me and said that if I didn’t get the visa at least three days before the JTT training, the scholarship would go to someone else. I asked her to give me two more days, and I would let her know.

Usually, without an appointment or phone call, they inform people about the visa. I had almost given up. I went to the Indian embassy to take my passport back, with or without the visa. I had prepared myself to tell Yogeswari to give the scholarship to someone else. But the person at the office told me I was very lucky my visa was ready, even before the 10-day minimum time they had said.

Until that moment, I hadn’t told anyone about going to India. I hadn’t even asked my manager, Abdel Halim Caracalla, for a month off. I immediately informed Yogeswari and asked my manager for a month’s holiday. At first, he said no because we needed to be in China after five weeks to perform seven shows. Then I asked his daughter, Alissar Caracalla, who used to practice yoga with Rima and knows Jivamukti, and he said yes.

I went to borrow Jivamukti books from a teacher who used to teach at Beirut Yoga Souk. I prepared myself in three days and went directly from the theatre after rehearsal to the airport. On the plane, I started reading the Jivamukti book, and during the teacher training, I delivered my essay.

At the end of 2018, I travelled with the Caracalla Dance Company to France to perform five shows. After the shows, I asked Caracalla for permission to stay in France and try my chance in Europe since my contract had ended, and Europe had always been a dream for me. I stayed a short time in Paris, then visited a close friend in Amsterdam

After a few months, I liked the city and asked a lawyer about applying for asylum. I was told it would take six months to get my papers, since I came from a war-torn country, and it would be clear why I couldn’t return. But those six months became 18 months. On top of that came the COVID-19 pandemic. During this time, I learned the basics of Dutch and began to understand the culture.

Through everything I went through, I managed to learn the language, complete my integration, and — after five and a half years — I got my Dutch passport in March 2025.

Since all these changes had happened, the revolution in Syria won, the regime failed it became for me a golden opportunity to see my family, even though Syria was still marked red as “unsafe.” For. The European travellers, I decided to go from March 31 to April 10. It was Eid al-Fitr.

At 7 a.m., I landed in Damascus, flying from Jordan. I stayed the night in Jordan because it was midnight when I arrived, and it was still not safe to drive.

From the window of the plane, I could see how old everything looked — at least 100 years or more. The people at the passport counter were different from when I used to travel with the dance company 14 years ago.

At Damascus Airport, no one asked me to carry my bags for money, no one made jokes about how I looked or my hair, and no one asked stupid questions like “What did you bring for me?” as a bribe. Taxis were lined up, everyone going in order. An old man drove me to my family’s house — I didn’t even know where they lived now because they had moved for safety reasons.

The first three days, I stayed at home, just listening to my family’s stories and seeing how much the country — and they — had changed. My parents were older, my sisters too. People in the streets looked tired and older, and even the buildings seemed exhausted. Coming from Amsterdam to Damascus felt like going back in time by 100 years.

When I went to the richer part of Damascus, I saw that not much had changed — but it was clear there were two worlds in this city: the poor, who looked tired and old, and the rich, who were still young and happy, as if there hadn’t been a war for 14 years.

I met my best friend, Nagham, who used to be my dance teacher and is still my closest friend. We had talked about this day for a year — where we would meet, what we would do. We almost cried. She was still there after marriage and had a beautiful daughter. Over dinner, I told her about my idea to do a workshop for dance students, what I wanted to do with them, and what they needed. She gave me ideas for everything.

The next day, I went to the Higher Institute for Drama and Arts, where I had studied and danced for seven years. It was also getting old. People there had changed — they seemed more aggressive. I didn’t dare to talk much, just asked questions and listened to their endless sad stories.

I met the head of the dance department, and we planned two workshops: dance and yoga. The next day, the students were simply told via a WhatsApp message: “Tomorrow, you have a workshop with Ahmad and another yoga session.”

When I saw the dance hall where I had learned ballet, modern, and contemporary, it also looked tired and heavy. There were four holes in the floor, covered with mattresses or chairs to warn students, or taped over with cheap black rubber. It was dangerous — a wrong landing could break someone’s leg. I didn’t even have to ask; I knew there was no budget.

The next day, I started with a warm-up for the third- and fourth-year students, then did the dance workshop with first- and second-year students. I asked them to “check in” like dancers do in the Netherlands, to say how they felt today. I saw hesitation on their faces — they didn’t know how to answer. It was the same for me when I had my first workshop with Christopher, a French teacher, in 2009.

I asked them to draw their feelings, then describe them with words. I turned their words into movements and used them to create short dance pieces in groups of two or three. They enjoyed it — young, full of energy, but also sadness. They were only 4–6 years old when the war started.

After 30 minutes, I gave a yoga class to the third- and fourth-year students. One girl asked me, “What is yoga?” She had never heard of it. I explained briefly, then we began. There was no electricity, so we used a small speaker. After shavasana, they stayed sitting, feeling the peace they had found. I could see both questions and good feelings in their faces. I didn’t chant “Om” at this first session.

The next day, they all came happy. I started with yoga for the first- and second-year students. After shavasana, they didn’t want to leave — they stayed 10 extra minutes to enjoy the calm. This showed me how much they needed yoga to relax their nervous systems. I felt sad afterwards, wanting to give more, but time was short.

My friend asked me, “What if it’s not allowed to teach yoga here?” I told her, “I’ll give it now, and if they ask me, I’ll just say I didn’t know.”

I repeated the same dance workshop for the other group. The students talked about how yoga had made them feel and how they woke up differently the next day. This time, I chanted “Lokah Samastah Sukhino Bhavantu” and “Om,” explaining them both.

It gave me great joy to teach what I had learned from yoga and dance to students who truly needed peace in their bodies and minds. After 14 years of survival, living with the minimum of everything — even food — one of the teachers told me he sometimes gave students money to buy food or even for transportation to come to classes. Even the teachers themselves hadn’t been paid for months. I was speechless after hearing all this.

I met a lovely new dancer who, I believe this porple will one day be a soloist and a professional in the world. And they will remember

Lokah Samastah Sukhino Bhavantu” and “Om,”

At the same time,

I am overjoyed with the yoga and dance workshops I held for the young dancers in Damascus. It fills me with happiness to know that I have planted seeds—seeds of flowers that will one day bloom, just as Azahar blossoms unfold to light up the world with their beauty and art.”